|

Back To Film Reviews Menu

|

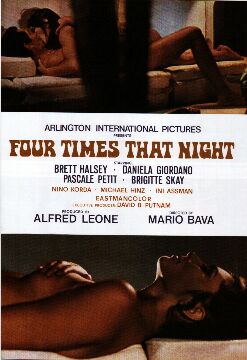

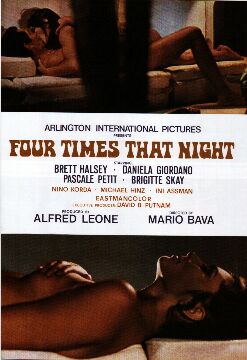

QUANTE VOLTE . . . QUELLA NOTTE (1969)

Director/Cinematographer: Mario

Bava

Story: Charles Ross

Screenplay: Mario Moroni and Mario Bava

Camera Operator: Antonio Rinaldi

Editing: Otello Colangelli

Music:

Lallo Gori

Main Players: Brett Halsey (John Price); Daniela Giordano

(Tina Brant); Pascale Petit (Esmerelda); Dick Randall (The Doorman);

Michael Hinz (George); Valeria Sabel (Mrs. Brant); Rainer Basedo (The

Milkman); Brigitte Skay (Moo-Moo)

Alternate titles: Four Times That Night

Aspect ratio:

1.85:1 |

SYNOPSIS:

Patterned after Akira Kurosawa's RASHOMON (1950), this film is a comic

dissertation on the nature of truth. The story deals with a

date-gone-awry and the different perspectives on what, in fact, lead to

Tina getting her dress torn and John ending up with scratches on his

forehead.

According to Tina, who is telling the story to her devoutly religious mother, John tried to rape her when she rejected his advances. The most

enjoyable of the four variations on the story, Bava has a lot of fun

turning this vignette into a contemporary take on "Little Red Riding

Hood." Tina, assuming the role of the wide-eyed, innocent virgin with a

mistrust of men (recalling Nora Drowson in LA RAGAZZA CHE SAPEVA TROPPO,

1962), spouts cliché after cliché, comically likening herself to Joan of

Arc and comparing John to the devil. She manages to escape "intact"

from her would-be seducer, but her mother is more concerned by the

damage sustained by Tina's expensive dress. . . According to Tina, who is telling the story to her devoutly religious mother, John tried to rape her when she rejected his advances. The most

enjoyable of the four variations on the story, Bava has a lot of fun

turning this vignette into a contemporary take on "Little Red Riding

Hood." Tina, assuming the role of the wide-eyed, innocent virgin with a

mistrust of men (recalling Nora Drowson in LA RAGAZZA CHE SAPEVA TROPPO,

1962), spouts cliché after cliché, comically likening herself to Joan of

Arc and comparing John to the devil. She manages to escape "intact"

from her would-be seducer, but her mother is more concerned by the

damage sustained by Tina's expensive dress. . .

Meanwhile, John offers his take on the matter when he runs into some of

his buddies in a bar. Here, John is a stammering, shy "nice guy" who

allows himself to be seduced by a beautiful girl. He describes Tina as

being an "insatiable, over-sexed piece of libidinous tail" whose sexual

prowess leaves him totally drained; she even scratches his forehead in

the heat of passion. John's fear of being sexually humiliated (he

objects to the fact that Tina is always one step ahead of him, so to

speak) is comical, but his vision of himself as a fly caught in a

libidinous spider's web is no more exaggerated than Tina's version.

Unknown to them both, the entire incident is being watched by a

voyueristic doorman, who has his own version to tell his good friend,

the milkman. In this version, John is a flaming homosexual who lures

Tina to his apartment with the promise of some casual sex. He has no

interest in her, however, and has only brought her there as a "gift" to

his lesbian friend, Esmerelda. By this time, the story has degenerated

into a literal orgy, an entertainment staged for the pleasure of the

nameless voyuer. As with the killer in SEI DONNE PER L'ASSASSINO, the

doorman is less a character than a means for Bava to comment on the

relationship between spectator and spectacle, or in this case

pornographer and pornography. He is distanced from the action, like the

viewer, and forced to see everything through a pair of binoculars. By

refusing to give this character a name, Bava turns him into a kind of

everyman. Though he is disgusted with the excesses of "kids today"

(marijuana, sex, pacifism), he is ultimately the most unsavory character

in the film. In making this slovenly drunk of a pornographer the symbol

of the old world, Bava rejects the notion of the "good old days."

Characteristically, the doorman draws the characters as broad

stereotypes. John is depicted as a lisping, limp-wristed "pansy" who

dupes Tina into having sex with his lesbian friend. Esmerelda, the

photographer, is a cunning sexual predator who promises to open Tina's

eyes to a new level of experience, promising that she "will never be

hurt by a man again." The macho image of homosexuality as an obscene

perversion comes through when Esmerelda remarks "One man is ugly, but

two are absolutely disgusting." The more male-oriented fantasy

oflesbianism is eroticized, but the doorman's puritanical stance comes

through by depicting Tina as a "nice girl" who is disinterested in

Esmerelda's fantasies. The segment concludes with an orgiastic

spectacle typical of a Penthouse letter: John rapes Tina as his male

lover and Esmerelda look on with interest.

As in any pornographic or romantic expose, the real explanation is much

more innocent. John and Tina, in fact, are struck by love at first

sight after a chance meeting in a park and after a pleasant first date,

they make a quick stop over at his place. By mutual consent, they

decide to wait a while before consumating their relationship, but John's

attempts to take Tina home are thwarted when the front gate refuses to

open. Of course, the doorman is nowhere to be found (he is drinking

himself into a stupor as he fawns over a porno magazine), and when John

tries to give her a boost over the gate, Tina tears her dress and

accidentally scratches his forehead. Knowing that nobody will believe

such a crazy story, they decide to make up their own versions for

anybody who is interested.

CRITIQUE:

QUANTE VOLTE . . . is one of Bava's most unusual films. It does not

make much of an initial impression, but repeat viewings reveal a film

admirable for its insight and imagination. Like so many of the

director's films, it ultimately says a lot more about human nature than

is initially apparent. By treating the story as a light comedy, Bava

avoids the pretentious leanings of other directors while making some

very valid points about cinema, life, and sex. In the same way that his

horror films and gialli boadly tread thematic aread where few others

dare to go, only to be ignored because of their subject matter, so does

QUANTE VOLTE . . . run the risk of being misinterpreted as just another

light and fluffy comedy about sexuality in the swingin' sixties.

Bava's obsession with the deceptive nature of appearances once again factors into the scenario. The film's take on the "dating game" is at

once cynical and realistic: quite simply, John and Tina take an

interest in each other because of their physical appearances. Perhaps

it is more accurate to say that John is the one who really shows himself

to be obsessed with Tina's looks, while Tina warms up to him by virtue

of his charm and personality. In any event, Bava opens the film with

shots of John driving around town in his "custom made sports car" (one

of the things that really appeals to Tina), ogling at a variety of

girls. By the time he reaches Tina, John first sees her as she stands,

stooped over, while petting her dog. As he later tells his friends in

the bar, just the sight of her robs him of breath. This completely

natural, albeit shallow, reaction to human physicality is given an

additional twist as the film develops. John's (apparently) apocryphal

description of Tina keeps in line with this idea: the sexual predator

she reveals herself to be goes completely against his expectations.

Likewise, Tina's portrait of herself as a complete innocent dupes her

mother into thinking that John is an attempted rapist. Even the title

sequence plays along with this theme. The very first image is of an

ink-blot; different viewers might perceive it as being a butterful, or a

bat, or two lovers kissing, etc. Bava's obsession with the deceptive nature of appearances once again factors into the scenario. The film's take on the "dating game" is at

once cynical and realistic: quite simply, John and Tina take an

interest in each other because of their physical appearances. Perhaps

it is more accurate to say that John is the one who really shows himself

to be obsessed with Tina's looks, while Tina warms up to him by virtue

of his charm and personality. In any event, Bava opens the film with

shots of John driving around town in his "custom made sports car" (one

of the things that really appeals to Tina), ogling at a variety of

girls. By the time he reaches Tina, John first sees her as she stands,

stooped over, while petting her dog. As he later tells his friends in

the bar, just the sight of her robs him of breath. This completely

natural, albeit shallow, reaction to human physicality is given an

additional twist as the film develops. John's (apparently) apocryphal

description of Tina keeps in line with this idea: the sexual predator

she reveals herself to be goes completely against his expectations.

Likewise, Tina's portrait of herself as a complete innocent dupes her

mother into thinking that John is an attempted rapist. Even the title

sequence plays along with this theme. The very first image is of an

ink-blot; different viewers might perceive it as being a butterful, or a

bat, or two lovers kissing, etc.

QUANTE VOLTE . . . hinges on the idea of truth. Things are seldom as

they appear to be in Bava's work, and here the viewer is presented with

a barrage of information, with little or no chance of coming to grips

with a totally accurate representation of the truth. The character of

the psychologist, who exists outside the scope of the narrative, and who

seems to be confined to a sterile laboratory setting,proposes the

John/Tina date story as a mere hypothesis. The scenes involving this

character are very unusual. They initially seem strange and disjointed,

strewn as they are through the final part of the film for no apparent

reason. Following the doorman's take on the story, Bava introduces the

psychologist for the first time. It is he who proposes to uncover the

truth of the matter, yet as the film draws to an end, Bava turns things

completely upside down. A long shot of John's car as he and Tina speed

off down the road is suddenly interrupted by the appearance of an

enormous, God-like hand which summarily picks up the car and pulls it

out of frame. The next shot finds the psychologist slyly grinning,

while holding a toy car in his hand. With that he addresses the camera

and asks the all-important question, "Do you really believe that things

went exactly in this way?" This totally unexpected, out-of-left-field

ending proposes a number of different questions. The viewer has, to

this point, been led to believe that he/she has been watching an actual

event. However, this is simply another of Bava's imaginative tricks.

Not only is the story not for real -- proposed as it is by the God-like

figure of the psychologist -- but the veracity of the psychologist's

final explanation has been called into question. Apart from offering a

nice, self-reflexive commentary on the superficiality of the cinematic

medium (the story, even without this final twist, is still not for real

-- it's only a movie), Bava ultimately refuses to allow the viewer

perfect clarity. In art, as in life, the truth is obtuse and clouded:

total, objective understanding is a foolish and misleading construct.

This film marks the first of three collaborations between Bava and American producer Alfredo Leone. In an effort to lend the film some

much-needed validity, Leone cited the film as "the film that opened the

gateway to justifiable nudity" in the liner notes he supplied to Elite

Entertainment for the laser disc release of GLI ORRORI DEL CASTELLO DI

NORIMBERGA and LISA E IL DIAVOLO. At first this claim seems

over-stated, but the key word is "justifiable." Certainly, Bava hates

to indulge in nudity in his own films, though he was sometimes forced to

compromise on this issue in later films. yet, even in those later

instances, he has it his own way by filming nue scenes to suggest acts

of voyuerism -- those who become aroused by these scenes are therefore

reduced to peeping toms. In this film, however, the subject matter

demands frank treatment of sexuality. It is when one considers Bava's

thematic approach to the nude scenes that Leone's claims begin to make

sense. In the first story, there is no nudity, keeping in line with the

fact that Tina is telling the story. By the time the film gets to the

doorman's version, Bava has taken the story into the sordid realms of

pornography, fetishism and sexual duplicity. The same can also be said

of John's version, to a lesser degree. Yet even in these two instances,

Bava refuses to succumb to cheap, sensationalistic ogling. The brief

nude scenes that are included are there for a purpose, and as Bava is

more concerned with the absurdities of modern life, he plays it all for

laughs rather than titillation. This film marks the first of three collaborations between Bava and American producer Alfredo Leone. In an effort to lend the film some

much-needed validity, Leone cited the film as "the film that opened the

gateway to justifiable nudity" in the liner notes he supplied to Elite

Entertainment for the laser disc release of GLI ORRORI DEL CASTELLO DI

NORIMBERGA and LISA E IL DIAVOLO. At first this claim seems

over-stated, but the key word is "justifiable." Certainly, Bava hates

to indulge in nudity in his own films, though he was sometimes forced to

compromise on this issue in later films. yet, even in those later

instances, he has it his own way by filming nue scenes to suggest acts

of voyuerism -- those who become aroused by these scenes are therefore

reduced to peeping toms. In this film, however, the subject matter

demands frank treatment of sexuality. It is when one considers Bava's

thematic approach to the nude scenes that Leone's claims begin to make

sense. In the first story, there is no nudity, keeping in line with the

fact that Tina is telling the story. By the time the film gets to the

doorman's version, Bava has taken the story into the sordid realms of

pornography, fetishism and sexual duplicity. The same can also be said

of John's version, to a lesser degree. Yet even in these two instances,

Bava refuses to succumb to cheap, sensationalistic ogling. The brief

nude scenes that are included are there for a purpose, and as Bava is

more concerned with the absurdities of modern life, he plays it all for

laughs rather than titillation.

Ultimately, QUANTE VOLTE . . . cannot rank as one of Bava's major works,

despite its many fine points. Though densely structured and

imaginatively directed, the film lacks the exquisite sense of style and

mood that typifies Bava's best work. It is simply a diversion -- and a

very charming one -- that finds the director waiting for his next fully

realized project. Yet in the mean time, he would be forced to undertake

another survival project for which he had no feeling, before embarking

on the last creative burst of his career.

Review © Troy Howarth

Back To Film Reviews Menu

|

According to Tina, who is telling the story to her devoutly religious mother, John tried to rape her when she rejected his advances. The most enjoyable of the four variations on the story, Bava has a lot of fun turning this vignette into a contemporary take on "Little Red Riding Hood." Tina, assuming the role of the wide-eyed, innocent virgin with a mistrust of men (recalling Nora Drowson in LA RAGAZZA CHE SAPEVA TROPPO, 1962), spouts cliché after cliché, comically likening herself to Joan of Arc and comparing John to the devil. She manages to escape "intact" from her would-be seducer, but her mother is more concerned by the damage sustained by Tina's expensive dress. . .

Bava's obsession with the deceptive nature of appearances once again factors into the scenario. The film's take on the "dating game" is at once cynical and realistic: quite simply, John and Tina take an interest in each other because of their physical appearances. Perhaps it is more accurate to say that John is the one who really shows himself to be obsessed with Tina's looks, while Tina warms up to him by virtue of his charm and personality. In any event, Bava opens the film with shots of John driving around town in his "custom made sports car" (one of the things that really appeals to Tina), ogling at a variety of girls. By the time he reaches Tina, John first sees her as she stands, stooped over, while petting her dog. As he later tells his friends in the bar, just the sight of her robs him of breath. This completely natural, albeit shallow, reaction to human physicality is given an additional twist as the film develops. John's (apparently) apocryphal description of Tina keeps in line with this idea: the sexual predator she reveals herself to be goes completely against his expectations. Likewise, Tina's portrait of herself as a complete innocent dupes her mother into thinking that John is an attempted rapist. Even the title sequence plays along with this theme. The very first image is of an ink-blot; different viewers might perceive it as being a butterful, or a bat, or two lovers kissing, etc.

This film marks the first of three collaborations between Bava and American producer Alfredo Leone. In an effort to lend the film some much-needed validity, Leone cited the film as "the film that opened the gateway to justifiable nudity" in the liner notes he supplied to Elite Entertainment for the laser disc release of GLI ORRORI DEL CASTELLO DI NORIMBERGA and LISA E IL DIAVOLO. At first this claim seems over-stated, but the key word is "justifiable." Certainly, Bava hates to indulge in nudity in his own films, though he was sometimes forced to compromise on this issue in later films. yet, even in those later instances, he has it his own way by filming nue scenes to suggest acts of voyuerism -- those who become aroused by these scenes are therefore reduced to peeping toms. In this film, however, the subject matter demands frank treatment of sexuality. It is when one considers Bava's thematic approach to the nude scenes that Leone's claims begin to make sense. In the first story, there is no nudity, keeping in line with the fact that Tina is telling the story. By the time the film gets to the doorman's version, Bava has taken the story into the sordid realms of pornography, fetishism and sexual duplicity. The same can also be said of John's version, to a lesser degree. Yet even in these two instances, Bava refuses to succumb to cheap, sensationalistic ogling. The brief nude scenes that are included are there for a purpose, and as Bava is more concerned with the absurdities of modern life, he plays it all for laughs rather than titillation.